45 Years Later: Celebrating William Lustig's Maniac

I told you not to go out tonight, didn't I? Every time you go out, this kind of thing happens.

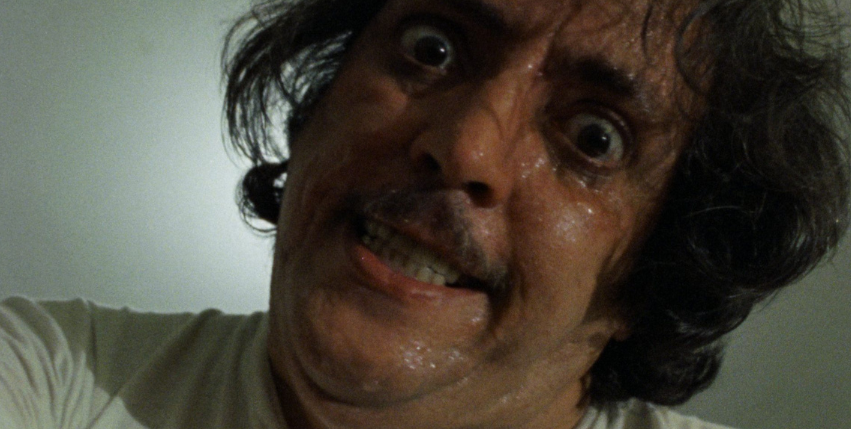

With its voyeuristic opening where an unseen assailant watches a young couple on a beach before mercilessly slaughtering them in cold blood, William Lustig’s grimy and gruesome slasher Maniac burst onto the scene at a time when American slasher movies were a relatively bloodless affair. A shockingly brutal character study of the lasting effects of childhood trauma that’s anchored by a desperately disturbing performance from Joe Spinell, Maniac remains one of the most notorious horror movies ever released, with a legacy that continues to live on even after more than 45 years.

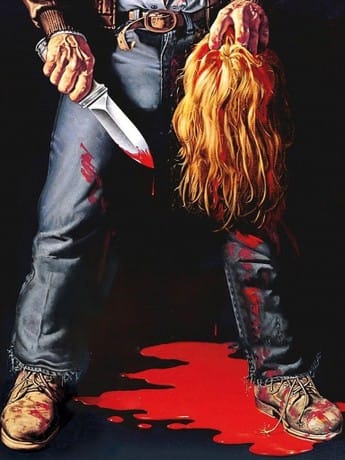

In Maniac, we follow troubled New Yorker and “artist” Frank Zito (Joe Spinnell) as he stalks a variety of victims and claims their scalps (and more) to attach to his mannequins so that he can create his own collection of women. Not a film looking to rattle you with jump scares, Maniac is an often grotesque and unflinching portrait of the violence we inflict on others, in all its forms, as it leaves you rattling around inside the head of Spinnell’s serial killer for nearly 87 minutes straight.

In a 2019 interview, Lustig discussed with me how the initial inspiration behind Maniac came from an unlikely source: Steven Spielberg. “The idea for this film came from an actor friend of mine, Frank Pesce [who would play a minor role in Maniac as a TV reporter]. We were driving down 8th Avenue one night, and he said to me, ‘Why don’t you do Jaws on land?’ And that sparked the idea for Maniac; in fact, the opening scene on the beach was my homage to Jaws.”

“But I met with Joe Spinell, and the idea we came up with was that there was this monster that was inside of this person, and he had this insatiable appetite for killing that just kept driving him. Joe wanted to play the guy who was struggling with that monster.”

And that’s the thing about Frank Zito — there’s no denying that he is a despicable character, but there is so much more to him than his internalized misogyny or relentless bloodlust for female victims (in fairness, we do see Frank kill a few guys as well, but more on that in a bit). Just existing as a human being is a major challenge for Spinnell’s character, and it’s evident that the abuse that his mother inflicted upon him throughout his childhood is something that Frank cannot get past.

In Maniac, Frank is still angry that his mom, Carmen, was so cruel to him, but you have to wonder just how much of her own life experience as a sex worker influenced her child-rearing skills over the years as well. We see on her tombstone that she lived sometime between 1907 and I believe the late 1950s (it’s hard to make out the exact year of death but there’s definitely a 5 in there), and I can’t imagine women of certain professions had an easy go of things back then, which meant she also probably had a rough go of things before she died in a car accident, leaving Frank to worth through the trauma all by himself.

And while we “hear” Carmen verbally accost her son (via some of Frank’s mental flashbacks), we also know that she physically abused him too, as he still bears the scars from her handiwork after all these years (he also suffers from headaches as well). There’s a scene where Frank tenderly touches his scars as he looks in the mirror, and you have to wonder if those caresses are the only positive and authentic expression of physical contact that Spinnell’s character has experienced in some time, or maybe ever.

Even though the story of Maniac is often a heightened exploration of one man’s capacity for depravity, Spinell was interested in taking a thoughtful approach to his role in the film and grounding his character Frank Zito’s twisted behaviors in a severe real-world issue: childhood abuse. Joe also used other real-world inspirations for some of his characters’ physical mannerisms.

“One night we were up in Bill Lustig’s apartment, and Joe was looking out the window at the building across the street,” Tom Savini recalled in a 2020 interview I did with him about the film’s effects. “Across the way, there was a kid in there, sitting on a couch or something, rocking back and forth. He was all by himself, rocking back and forth, and that’s all he was doing. So, when Joe saw that, he incorporated that into his character. It was also Joe’s idea that Frank would have all these scars all over him, which had been given to him by his sadistic mother.”

“Joe was very passionate about incorporating childhood abuse into this story because it was an issue that was still very much in the closet at the time. So, throughout production, we were always throwing ideas around between the three of us [Lustig, Savini and Spinnell]—it was great, and I think that’s part of the reason why the film works as well as it does.”

Frank’s inner turmoil is what makes Maniac so much more than just another early ‘80s slasher looking to shock moviegoers. His acts of violence aren’t celebratory in nature; he seems genuinely conflicted and remorseful. Sometimes Frank even cries after he claims another victim. Early in the film, Frank goes into a hotel with a lady of the night for what she thinks will just be another job with a John. But of course, Frank murders her before they even get things started, and I think it’s interesting that Spinnell’s character immediately throws up as a result of his own actions.

Frank is a character that isn’t afraid to get emotional in Maniac either. We see Spinnell shed quite a few tears throughout the film, and while I get that his character isn’t exactly the portrait of a well-adjusted person by any means, it does demonstrate that Frank is someone who hasn’t bought into the concept of “real men shouldn’t cry” which was pervasive throughout society at that time.

There’s also a sense of longing that is just eating away at Frank where know that he has this desperate desire to just be “normal” that he will never be able to fulfill. There’s the scene in Maniac when he’s admiring all of the female mannequins in the store front windows, particularly the one dressed as a bride, and Frank’s sadness is nearly palpable there. To him, those figures represent a life he will never get to experience (which is why he has to make his own collection of women inside of his apartment).

We also see that aspect of Frank’s character come out in the film’s opening, when he murders a couple on the beach, and we see it again when he hunts down Disco Boy (played by Tom Savini, who relished being able to blow up his own head for Maniac) and Disco Girl (Hyla Marrow) after they leave the club Blossoms together and head out for some backseat hanky panky near the Verrazzano-Narrows Bridge. This scene was also inspired by the “Son of Sam” murders that terrorized New Yorkers in the late 1970s, which is yet another way Lustig was able to infuse Maniac will these raw and real elements that make it so effectively unnerving as a viewer.

These acts of violence stem from Frank’s own belief that he’ll never find happiness and is doomed to be tortured by women due to how his mother treated him. If you’re own mother can’t even love you, how can anyone else be expected to? But we see that once Anna D'Antoni (Caroline Munro) enters the picture, Frank actually had a chance to achieve the normalcy he was so desperately craving. In many ways, Frank and Anna would be the perfect couple: they both have a deep appreciation for art — especially the female form — and there’s instant chemistry between them as well.

Anna doesn’t judge Frank at all when they first meet, and she’s even game to spend time with him socially. She even invites him to one of her photo shoots, and I love just that in the scenes that Spinnell shares with Munro, he’s a completely different version of Frank. He’s smooth, he’s confident and he almost has a swagger to him — pretty much like Frank himself is putting on a performance of what he thinks he should be in order to spend time with this woman who he clearly admires and connects with.

But that facade begins to slip — first, we see it as he’s sitting at her photo shoot, and Frank’s body language just subtly begins to change as he’s watching the women that Anna is shooting, especially Rita, played by Gail Lawrence. Frank decides to steal a necklace at the shoot so that he has an excuse to make contact with Rita later that night, and he ends up claiming her for his collection.

Somehow, Frank manages to continue to maintain a civilized presence around Anna though, as he not only sends flowers to Rita’s funeral but attends it as well so that he can appear supportive of Anna’s own grief. The veneer that Frank wears around Anna completely crumbles though once he asks her to visit his mom’s grave and ends up revealing that he was the one who murdered Rita after he losses while praying.

From there, Frank’s inner turmoil manifests itself in some telling ways. First, he imagines that his mother emerges from her grave to attack him (in a sequence that Lucio Fulci would be proud of), and then when he gets home, Frank believes that his mannequins have come to life and are hellbent on getting their revenge on him by dismembering his body and decapitating him in Maniac’s most gruesome sequence.

Spinnell’s performance in Maniac is so beautifully nuanced and layered in unexpected ways which is part of the reason why Lustig’s Maniac made such a huge impression on genre fans when it was released in the early ‘80s (it premiered at Cannes in 1980 but didn’t begin making its way into theaters until 1981), and it has become a well-regarded cult classic these days as well.

While Maniac might feel like a grimy exploitation flick at first glance, there’s really so much more happening in the film and that is due to Joe Spinnell’s thoughtful approach to this character that should be completely repulsive, and yet, is a somewhat heartbreaking portrait of the detrimental effects of parental trauma. Maniac’s ability to create this narrative juxtaposition where we feel bad for someone who has been clearly abused but their own outright contempt and cruelty keeps us from ever fully exonerating that character of their crimes isn’t an easy line to walk but it’s a huge reason why the film stands out from other movies that share a similar storytelling approach and has become a favorite of mine over time.